“You probably think you could paint this, don’t you?”

My art history teacher scanned the room, green eyes sparkling.

Madame Boulay used an ancient slide projector that whirred and clanked. She stood at the edge of the screen, the projector lighting up half her face. With one pupil the size of a pin prick, she looked a little crazed. “Regardez ceci.” The screen flashed from dark to bright as the drum turned. A red-orange Rothko slide thunked into place.

“A five-year-old could do this, right?”

I observed the messy rectangles of color. It looked elementary, I thought.

“I’m going to convince you that you’re wrong,” she said.

I sat back, skeptical but intrigued. I eyed the screen again, considering the misshapen planes of color. How could that be meaningful? Convincing me seemed like an impossible task.

More than 15 years later, I was at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, tears in my eyes, face to face with that Rothko.

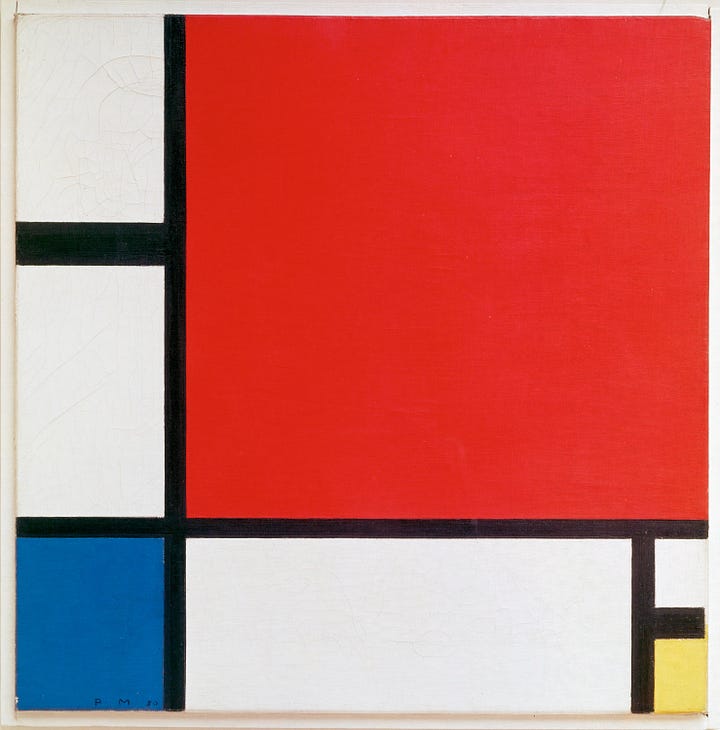

The canvas stands eight feet tall, drawing you inside the horizons of red and orange. I was transported back to that dark classroom in France. I had run away from my liberal arts degree, acting out of helpless romanticism. Feckless and unsure of myself, I was taking random art history classes, yearning, searching for direction. Over the course of the semester Madame Boulay taught me about Brâncuși, Mondrian, Klein, and Matisse. I learned about nouveau réalisme, color field, surrealism, and dada.

Now in my late 30s, I’d lived lifetimes since that semester in France. Did I have anything to show for it? Hot tears wobbled on the edge of my lash line. I’d just quit my agency job after seven years. I was directionless again, taking random trips to New York on romantic whims, searching.

Burnout is a bitch. It felt like a concussion. Like cotton stuffed in my ear canals and wedged at the back of my optic nerve, everything dulled with indecision. I was in New York looking for some spark, some sign of where to go next. Yearning feels less romantic as you approach 40, it just feels tragic.

But the Rothko was soothing me. I stood nose to nose with the canvas, allowing the oranges and reds to wrap around my peripheries, feeling the paint textures like fabric against my skin. I felt cooled, the heat and stress of burnout softening as I let the canvas give me a new horizon line, a new point of view.

Funny that following the whims of my stuffed up, burned out brain led me here, to this painting, thinking about the cunning Madame Boulay.

Since taking her class, I’ve turned her question over and over in my mind. Could I do something as magnificent, and as simple, as a Rothko? How does an artist achieve that purity of vision? Would seeing like an artist help me see more clearly?

Meet Kendric

Kendric Tonn is a professional oil painter in Columbus, Ohio. Although he specializes in portraiture and still life, you may know him as the guy who won the Rothko argument on Twitter. Funnily enough, he doesn’t even like Rothko that much.

So who are his favorites? He shrugged shyly, “Most of them are very obvious names.” He listed Sargent, Rembrandt, Bruegel, and a penchant for pre-Raphaelites. But I also know that Kendric wrote a thread of 500 paintings he likes. His repertoire is extensive and impressive and in no way “obvious”.

When he told me the story of how he became a classical oil painter, I was agog. The guy was an English major, surrounded by nerdy computer science friends, but couldn’t stand a life in academia or tech, so he ran off to Italy to study art.

“Christ, that's romantic,” I said, feeling kindred.

“Perhaps people prone to romanticism are more likely to run off to Italy to study painting,” he said with a half smile. “Or perhaps it’s the other way around. I'm not sure in what direction that flows.”

When he arrived at the Florence Academy of Art, he wasn’t allowed to touch printing blocks or acrylics or oils. First, he had to draw a foot.

“I spent two weeks drawing the same foot,” he said. “It was a very simple foot with a very clear sense of light and shadow and form. And I would get a critique every morning. The teacher came in and was like, no, your ankle is one pencil width too wide. Please correct your ankle.”

The atelier had a 19th-century teaching style, using the same exercises that came from Paris in the 1870s. Copying lithographic plates. Figure drawing. Live models.

“My early training focused on how to find shapes,” he said. “The shape of shadow falling down someone's cheek, the abstract patterns, the sculptural elements, the weird convoluted forms of the world around us.”

Seeing the world in shapes demands that you override your brain’s predictive processing. Instead of classifying everything in your environment as “person” “chair” “table,” Kendric said, “You have to drill down, you have to get closer to the metal.”

The Eye

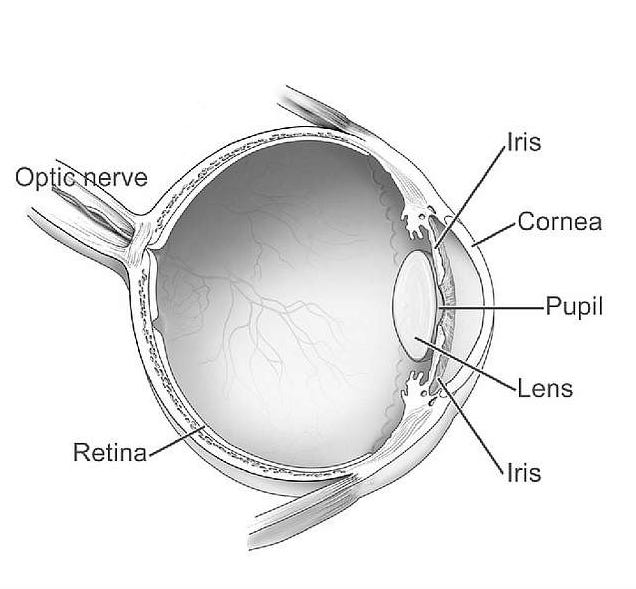

The eyeball is a miraculous organ. The human eye can distinguish up to 10 million colors, and contains 126 million light-sensitive cells (120 million rods, 6 million cones).

What exactly happens in there? Let’s review.

Light passes through the cornea, the dome-shaped outermost layer of your eye, through the pupil, your eye’s aperture. The iris, the lovely blue, green, or brown part of the eye, is actually a mass of slick mucosal muscles responsible for dilating and constricting the size of the pupil. The light then passes through the lens, a translucent gummy-candy ovoid, responsible for bending and focusing the stream of light.

Light travels through the inside of the eye, filled with vitreous gel to maintain the ball shape and provide a clear cavity for light to pass. These bending light waves then hit the eye’s curved back wall, the retina, a layer of tissue lined with photoreceptor cells (rods for low-light vision, cones for color vision). The photosensitive cells of the retina turn light into electrical signals. These signals travel through the data cable of your optic nerve to the brain, where the information is interpreted as images.

Although the process takes only milliseconds, that is too long to wait.

Predictive Processing

The work to convert these optic nerve pulses into coherent information is a heavy cognitive task. Instead of interpreting all the environmental stimuli every moment, we use predictive processing to speed up the procedure.

In “Radical Predictive Processing,” professor Andy Clark writes that neuroscience experienced a “Bayseian flip” in recent decades. The traditional theory, which held that our perception of reality is created bottom-up by collecting visual stimuli to build an image in real-time, was overturned.

Instead, predictive processing (also known as “hierarchical predictive coding”) suggests the brain creates a top-down “generative model” of reality. The model is built on prior knowledge of your environment—in effect, old information—creating a “controlled hallucination” inside your mind. However, this reality projection is under constant scrutiny. As you look around the room, your model of what you expect to see is updated to integrate novel information or discrepancies. Your brain, Clark writes, is working to “reduce prediction errors” based on the “evolving shape of the sensory barrage.”

Scott Alexander, in his book review of Clark’s Surfing Uncertainty, summarizes it like this: “You’re not seeing the world as it is. You’re seeing your predictions about the world, cashed out as expected sensations, then shaped/constrained by the actual sense data.”

Predictive processing thereby reduces the cognitive load of bottom-up processing, so that the brain saves energy and pays attention only to novelty and danger.

An effective evolutionary feature for a homo sapien hunting on the savannah. Not so effective, however, for an artist. The predictive processing of the brain is so powerful, artists like Kendric have to train for years to override it.

“Learning to see is the awareness of what is actually hitting your eyes, as opposed to what your brain decides about that information,” he said.

“We walk around thinking we're seeing things with individual discrete identities. But actually all of that is just names we’ve given to a jumble of blobs and color. In a sense, there is no image of the person. There's just light and darkness.”

Dissolving the Edges

In Madame Boulay's classroom, looking at canvases of light and darkness, she taught me why I should care. She taught me to see the abstraction, distillation, gesture, and emotion.

I remember the slide of Brâncuși’s Bird in Space, and Mondrian’s Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow. I learned how the artists removed, distilled, and simplified until only the purest form was left. A simple shape to communicate the richest and profoundest of feelings. Taking apart each artwork, I was taking apart myself as well. Removing my judgments, my self-consciousness, my expectations, my fear of failure layer by layer.

The artists are inviting you in, they’re asking you to see differently, put down your projection of reality and see something new. “You have to let it in,” Madame Boulay said, “you have to surrender.”

To paint an image, Kendric told me, you have to surrender to the abstraction. In order to override the mental models your brain has built, you have to lose the edge, dissolve the borders of things, and experience the world as “blobs of color and light”.

Many new artists want to draw a line around everything. “People really want to have that cohesive border, that hard edge, that line around the object,” he said. “Losing edges is a hard thing to do. We’re very resistant to it.” Losing the edge takes trust, a leap of faith to leave behind reality as you know it.

How to do this? Kendric had some suggestions. “There are some mechanical gimmicks,” he said, “like squinting.”

“You can just squint. Squint down really, really hard and now the world is just blurry shapes.” I took a second and tried it. Squeezing my eyes down until my lashes nearly crowded out the picture. A smoked mirror does something similar, he said, “it darkens everything down and leaves you with big blobs.”

Or, looking at something upside down, “that’s a classic one,” he said. “Upside down it's hard to immediately latch onto those pre-interpretations. So you're presented with this chaos of shapes.”

Postmodernist painter and art columnist David Salle writes, “How a painter treats this edge is the real subject of realist painting. How the brush behaves in the vicinity of an end gives a painting its present tenseness, the feeling of an eternal present.”

Instead of a line around each discrete object, the edges are built up from blobs of color arranged side by side until the image emerges. When a painting achieves that crackle of life, what Salle calls “eternal present,” you know you’re in the presence of a master.

Take Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait with Beret and Turned-Up Collar. “There is this real sense of psychological presence,” Kendric said. “There is a sense of another living entity in front of you.”

That glint of the eye is something a painter can spend his whole lifetime trying to achieve. “There's no formula to it,” Kendric said. “It's often the difference between a quarter millimeter—between a dead fish eye and a living eye.”

Curiosity and empathy, Kendric said, are the necessary ingredients. He has to stay present with his subject, really seeing them for who they are.

“When you paint a portrait, you’re forming a still image built out of three, or 12, or 50 hours with someone. It's always a composite image—a smeared out moment in time.”

“When you start getting to know them, you can see different things, just like the face of a friend shows you more than the face of a stranger,” he said. “You can't paint what you can't see.”

Immediately after my interview with Kendric, I slung my feet over the back of the couch. Just turn upside down? It seemed silly and fun, almost too simple.

It only took a second for my brain to adjust, but in that nanosecond of confusion—in an objectless world of light and dark, blobs and color—I experienced something pure and perfect. The present moment.

And that’s when it clicked.

How to See

Artists challenge the old information in our generative models. By presenting familiar subjects in new ways, artists force us to update our perceptions. They inject novelty and discrepancy into our “sensory barrage”. Art absolves our expectations. Art jolts us into the present moment.

But artists aren’t the keepers of How to See secrets. You don’t have to paint a canvas to see more clearly, you can just flip upside down, or sing, or pray, or meditate.

There are many traditions of philosophy, religion, and psychology that reach similar revelations. Stoicism, mysticism, and even mindfulness therapies have so much in common in this way—they all strive for a greater sense of clarity and inner peace. I especially love the Buddhism lens. Buddhists seek to transcend the ego and attain a direct, personal experience of the ultimate reality.

“In order to truly see, you need to dissolve the signs and perceptions.” If you didn’t know Thich Nhat Hanh was a Buddhist master, you might think he was an art critic or a neuroscientist. He writes in How to See, “We paint the new information with the old colors we already have inside us. This is why most of the time we don't have direct access to reality, to things as they are.”

Buddhism teaches the importance of seeing through the illusions of form, self, and separateness to directly experience the interconnectedness of the world. This is a path to “ultimate reality”. From Hanh: “All views are wrong views. Any view is just from one point. We need to continue expanding the boundaries of our understanding, or we will be imprisoned by our views.”

Expanding my boundaries was exactly what I was looking for at the MoMA. I wanted to break out of my burned out brain. So when I turned a corner and came face to face with Rothko’s No. 5/No. 22, I gasped.

The synesthetic memories were deafening. I was back in Madame Boulay’s classroom. I could smell the chalk dust, the hot air from the projector fan. I fell towards that previous version of myself. That young student who longed to be as confident and knowledgeable as her art teacher. That skeptic who desperately wanted to understand.

I took a deep breath, and planted myself right in front of the canvas. I was rocketed into the present moment, swept up in the canvas’s motion and grace, the weightlessness, the awe.

Soothed by the tones and textures, my judgments and impatience fell away. I was reminded of a Hanh quote: “Love enables us to see. To practice looking deeply is the basic medicine for anger, hatred, and fear.”

Questions like “what am I doing here?” “what have I accomplished?” seemed inconsequential, the babblings of an anxious mind. I was released from the worry and indecision. I was floating in a color field, my edges dissolving.

Was this “ultimate reality”? Was this the void? Or was this simply the bliss of my brain shaking off predictive processing?

I’m not sure. But I felt the haze lifting. I walked out of the MoMA into the wall of noise of 5th Avenue, observing happily that the world is just blobs of color, light, and darkness.

I left New York without any answers. I’m still feeling concussed; I don’t know where I want to go in my career or how to decide, but I’m seeing the path forward like a canvas. A person, as Kendric told me, “is always a composite image—a smeared out moment in time.” I’ll keep adding bits of color and shape. I’ll work to get back in touch with my talents and purpose, and the image will emerge.

“You think you could paint this? I’m going to convince you that you’re wrong.”

I want to tell Madame Boulay that she was right. She did convince me. I can’t do what artists like Rembrandt, or Rothko, or Kendric do, but I can, for a moment, see through their eyes and surrender.

Stay tuned for the full conversation with Kendric, publishing next week! Did you miss the previous episode? Read the How to Taste essay, and watch the How to Taste podcast/video interview. See the full series here.

"Just a smeared out moment in time" ❤️

This is fantastic Emily. What a good insightful inspirational article.