I’m from Georgia, but I didn’t grow up eating fried chicken and collard greens.

In fact, my grandmother is a terrible cook, bless her heart. So I didn’t inherit a cherished biscuit recipe or fry okra in her kitchen.

I’m envious of food traditions with bold, culturally-salient dishes—like aromatic Indian curries or bright Mexican salsas. I’m curious how my sense of taste would be different if I’d grown up with stronger food role models. How plastic is our sense of taste? Could I improve mine?

My parents worked full-time, they were exhausted. Putting together a family dinner every night was a burden. We didn’t gather at the table expecting a culinary adventure, we gathered for the ritual. I held hands and sang grace, I kicked my brother under the table.

Instead of evening meals, my family’s food culture centralized around Christmas potlucks. My grandmother’s seven siblings and all the assorted cousins and uncles would gather in Ellenwood, GA.

My great aunt’s table would be covered in man-made wonders and horrors. There was a green jello mold with floating fruit and nuts, quaking as children ran through the house. The brain-like hump of pimento cheese dip with an array of dry crackers. A gray casserole made from canned green beans suspended in mushroom concentrate. The Brown n’ Serv yeast rolls would be burnt on the bottom, thanks to grandma. There would be a blue tin of crumbly butter cookies that tasted like vegetable oil, and the inevitable mayonnaise salads (waldorf, broccoli, macaroni) studded with raisins, sweating.

That is to say, we were poor.

My family goes four generations deep as humble, small-plot farmers south of Atlanta. For people who grew up kneading bread and milking cows, store-bought foods were indulgent, a signal of prosperity. But did these Christmas dinners actually taste good? Of course they did. Campbell’s mushroom soup? GOATed. Yeast rolls? Delicious, even when burned, and especially after absorbing waldorf runoff and gizzard gravy. Pimento cheese dip, though? Awful.

Don’t get me wrong, these are happy memories! But, I wanted to talk to someone who could help me expand my narrow palate stunted by jello and mayonnaise.

I’ve noticed that people with good taste have two things in common: curiosity and role models. I have plenty of one, but not the other. Adam Wong has both.

Meet Adam

People may know Adam as @cookingwong, a guy who tweets about space technology, astronomy, and beef jerky. Others may know him as a 2011 contestant on Master Chef, or a graduate from Harvard’s school of anthropology. But I know Adam because he roasted a whole pig at Vibecamp 2023. To my delight, I got a slice of cheek.

Adam started making chow mein at age five in the kitchen with his dad. “As a way to get out of homework,” he said.

His father, who is Chinese, did most of the cooking in the household. “He is an amazing cook. As a kid, I always looked forward to dinner—it looked like a lot of fun. Lots of banging, lots of chopping. I thought, ‘This is so much cooler than spelling.’”

His father taught him strong values around family, food, and culture. “The Chinese greeting is, ‘Have you eaten?’” Adam said. “Growing up with a gourmand dad, all we talked about was food—and World War II history—but mostly food. I had a very family-oriented food education early on. And then later he connected cuisine with history and geography and chemistry and all sorts of things.”

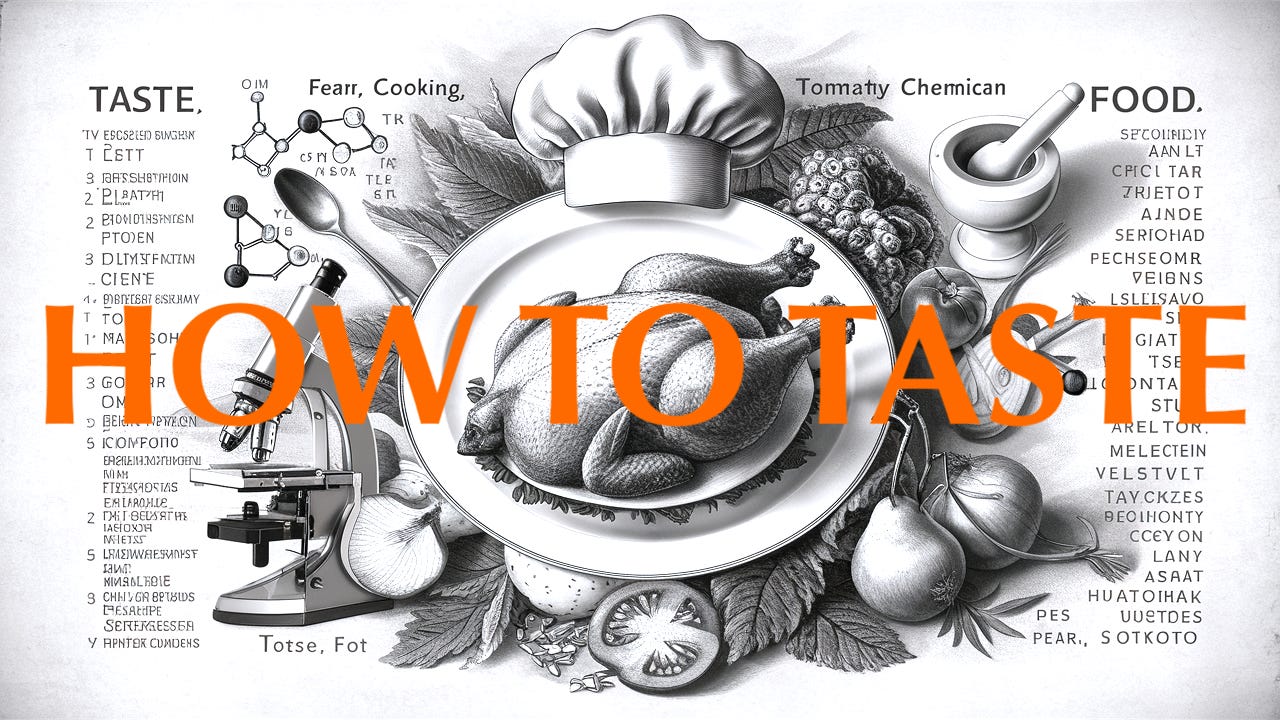

It doesn’t hurt that Adam is a supertaster. That means he literally has more taste buds than you. Humans have a range of 2,000 to 10,000 taste buds, with supertasters being at the top end. Additionally, they have a special gene: TAS2R38, which increases sensitivity to bitterness. Supertasters tend to be picky eaters, easily icked out by unexpected textures or highly bitter flavors. This is not the case for Adam.

His supertasting makes him a voraciously curious and adventurous eater. He’s explored everything from the truly revolting (fermented squid blood) to the playful and strange (kiwi ketchup on a papaya hotdog). But Adam doesn’t think his genes are solely responsible for his gift.

“I do have some genetic predisposition,” he allowed. “But I’ve also paid a lot of attention to it. Food really is the king of my sense palace.”

Taste v Flavor

Taste is one of the most complex and comprehensive senses. All of our senses work together to a degree, but taste draws heavily on our olfactory, sensory, and auditory systems as well.

“Taste is our most intimate sense,” Adam contended. “You're taking in this material, food: you see it. You touch it. You put it inside your body. You hear it crunch, not through your ear, but through your jawbone. You smell it wafting up through your nasal cavity. And most intimate of all, you're turning it into your body through metabolism. I’m eating this food and turning it into me.”

By this definition, it’s easy to see that “taste” isn’t a singular qualia. It’s a bloom of experiences happening simultaneously through the anatomy of your tongue, the chemical compounds of flavor, and the psychology of emotion and identity.

For me, learning to distinguish “flavor” from “taste” was a critical step toward understanding and improving my “most intimate sense”.

Flavor is a discrete set of chemical and biological phenomena. When you cook a food, it undergoes a chemical change, “a complexifying process.”

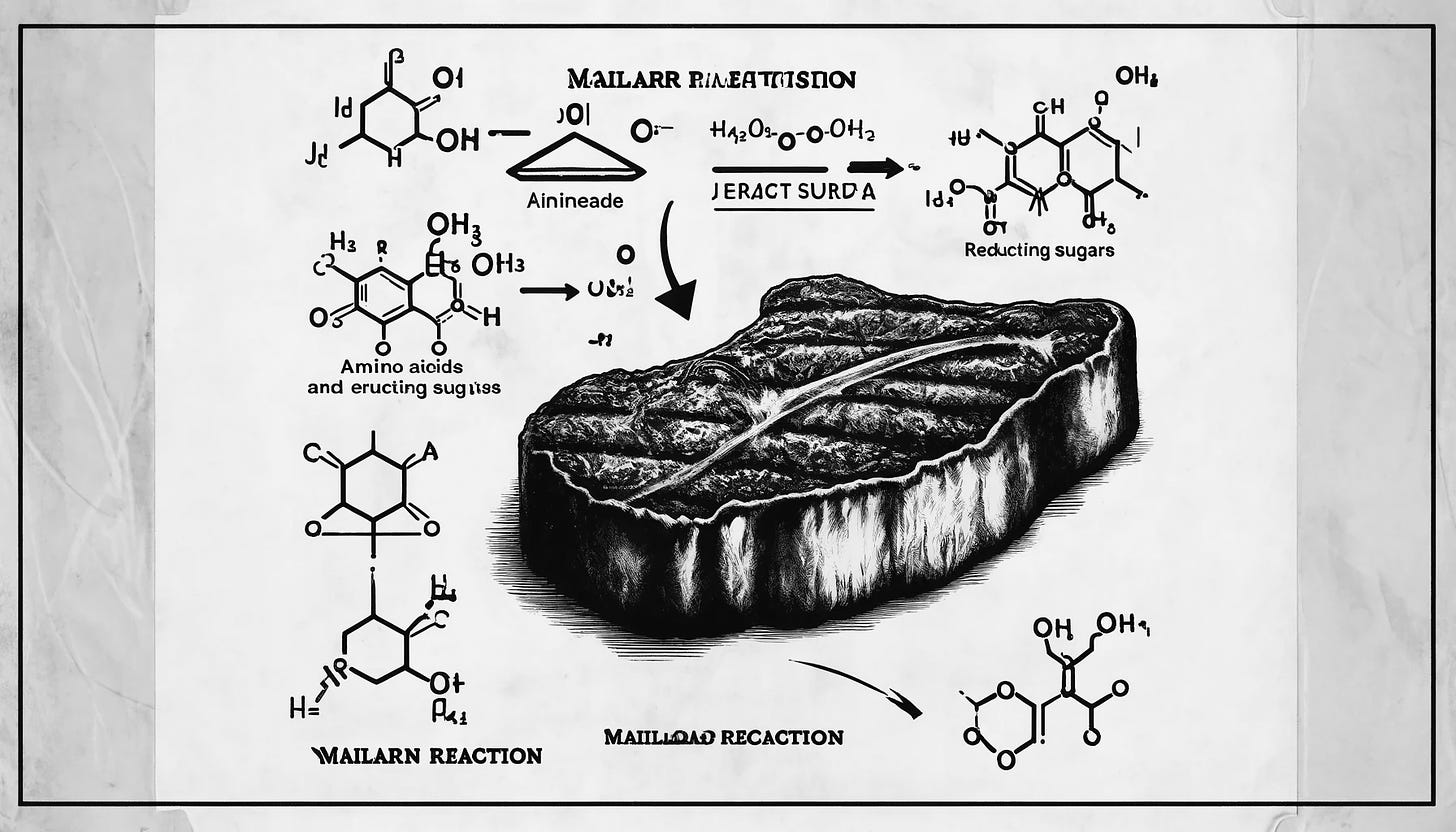

“You're taking something that is relatively homogenous, like a sheet of proteins, and you are heterogeneously heating them up and inducing a chaotic chemical change,” Adam said. “This is true for Maillard reactions. This is true for fermentation. This is true for wine aging and oxidation.”

The Maillard reaction is one of the most studied chemical reactions in food. “It’s the way you change a steak into a gourmet meal: you complexify. You change it from just being a steak, to the 40 other chemicals that pop up as a result of the Maillard reaction.”

If you’re new to this like me, here’s what you need to know about ol’ Maillard. Sugars react with the amino acids on the surface of food, creating an explosion of new chemical compounds responsible for flavor, aroma, color, and texture. The reaction is accelerated by low pH, exposure to air, and high heat, thus explaining why searing a steak or roasting vegetables changes the color and flavor so significantly.

As the Maillard reaction creates new flavor compounds, those new compounds react together, creating even more new compounds. This feedback loop unleashes infinitely branching flavor possibilities that modern scientists have yet to quantify.

“Chaotic chemical change” indeed.

“Flavor branches depend on the complexity of the food that you're starting with,” Adam said. “With broccoli you have the stalk, the leaves, and the flowers. Flowers are so complicated! Each part has different chemicals that then create their own flavor trees. Compare this to a filet mignon, which is prized for its homogeneity. With broccoli you actually have more surface area for chaos.”

Okay, so chaos creates flavor. But does flavor create taste?

How to Taste Better

Unfortunately, food can have wonderfully rich flavor, but it’s lost if we don’t have the skill to taste it. A tree falls in the woods, alas.

Adam reassured me that even if we’re not natural born supertasters, there are things we can do to enhance the experience and taste of food. With practice, we can even expand our preferences and widen our sensation of flavor.

Simply put, “Pay attention.” Adam said to focus on these main data points: temperature, texture, balance, quality, and context.

Take the reuben, for example, “The best sandwich on earth.”

Notice the temperature of the hot meat and cool sauerkraut; the texture of the toasted bread, melty cheese, and crunchy pickle; the balance of fatty pastrami, briney cabbage, and tangy mayo. All of this is enhanced by the quality of the meat, bread, and cheese, and the emotional context of the cozy pub with friends where you ate it.

As I’ve explored the five senses in this series, I’m amazed at how interdependent they are. Just as Bex described the sense of touch through color, and Reb described the sense of hearing through texture, Adam compared taste to a symphony. He encouraged us to pay attention to the qualities of food the way we would listen to a piece of music.

“In music, you need rests and quiet for you to appreciate the noise. So I think a steak needs an element like a salad. Steak is strong basso, lots of burnt flavors, earthy flavors, savory, fatty, and it needs a rest of something light, airy, relieving—like a vinaigrette salad.”

“I'm a balance guy,” he said. “The three biggest things I look for are novelty, balance, and Gesamtkunstwerk.”

Gesamtkunstwerk is a German loanword popularized by composer Richard Wagner, which translates to “total work of art” or as Adam says: “complete art”.

For a food to have Gesamtkunstwerk it needs emotional context. I told Adam I’d never considered the “set and setting” of a meal. His eyes grew wide, “Oh, it’s so important. Context can be more of a determining factor than flavor. Food is emotionally and socially contextual.”

So while flavor is determined by chemical reactions, taste is contingent, subjective, and altogether emotional. A growing branch of science called neurogastronomy is studying this connection between food chemicals and brain plasticity. Foods are potent mnemonic catalysts. Over the course of human evolution, we’ve been tuned to create long-term memories around high-reward foods.

“Imagine it's summertime, you're digging up clams at the beach and throwing them in the pot,” Adam said. “The sun's out. You’re cracking open a cold one. Your favorite music is playing and friends are throwing a frisbee around. Those are the most delicious clams you'll ever eat.”

Food creates a mnemonic cascade—a flood of memory and emotion encoded via dopamine and cortisol. Pleasurable foods create strong positive associations in the brain that can actually be mapped. As we eat a nourishing, delicious meal the hippocampus lights up alongside the taste cortex, encoding the emotional, geographic, and temporal aspects of the experience so we can reliably find that food again.

Similarly, the survival tactic conditioned taste aversion creates negative associations. It’s a learned response to poisonous foods—something you’re familiar with if you binged Tequila Sunrises as a freshman and “just can’t do tequila” anymore. The experience imprints an illness-taste association that prevents us from eating toxic foods (or mixed drinks) in the future.

This explains why you’d remember the taste of clams when you revisit that beach (positive), or why pimento cheese brings me childhood nostalgia (negative). Our brains are wired to remember the emotion, location, and time.

Adam said when food is a complete art, true Gesamtkunstwerk, all these elements combine. Chemical, physical, emotional. To become a supertaster yourself, no matter your tongue’s anatomy, all you have to do is practice paying attention. Sit down to each meal like a symphony, listening for the balance, texture, temperature, and emotional valence working in concert with each bite.

Food as Identity

As for me, I’m improving. With practice I’ve been able to taste the cardamom and cumin in a spice blend, or cherry notes in a red wine. And I understand those flavors are deepened by the set and setting of the meal.

I moved to San Francisco recently, and I threw a dinner party. In our apartment, still sparsely furnished, we set up folding tables and pulled in office chairs and stools. As our friends arrived and shook off their coats, our new home filled with voices and laughter. Even though I’d never eaten it as a child, I cooked a Southern favorite: shrimp and cheese grits. With Adam’s advice in mind, I whipped the grits until I achieved a creamy texture. I balanced the fatty cheddar with pickled jalapeno. The hot shrimp paired with cold marinated vegetables. The flavors came together like a song. I did burn the broccoli, but I gotta stay true to my roots.

We used every single dish in the cabinets—drinking wine from jam jars, and eating grits with soup spoons. Looking around my living room, surrounded by new friends in a new city, I knew that was the best shrimp and grits I would ever eat.

Adam put it like this: “Love your food. If you love your food, you will pay attention to it. By doing that you’re respecting yourself, respecting your community, respecting your world, and respecting the relationship between your brain and your body.”

At that dinner party I saw how taste is charged with social and cultural significance, far beyond the chemicals of flavor. Ultimately, taste is the most intimate sense because it constructs your identity and value.

Writing this article showed me I had both ingredients after all: curiosity and role models. My food role models didn’t teach me about World World II or cultural heritage. My busy parents, great aunts, and grandparents instilled a different lesson: a meal is a precious moment of togetherness. Sharing food is a time to be grateful for the abundance you have, no matter how humble. With enough attention you can develop a taste and gratitude for food in all forms—even pimento cheese.

Stay tuned for the full conversation with Adam, publishing next week! Did you miss the previous episode? Read the How to Hear essay, and watch the How to Hear podcast/video interview. See the full series here.

Delectable read! 😋 How do I find out my tastebud count??