The molecule Methylbenzodioxepinone (“calone”) was first synthesized in 1966. It smells like air.

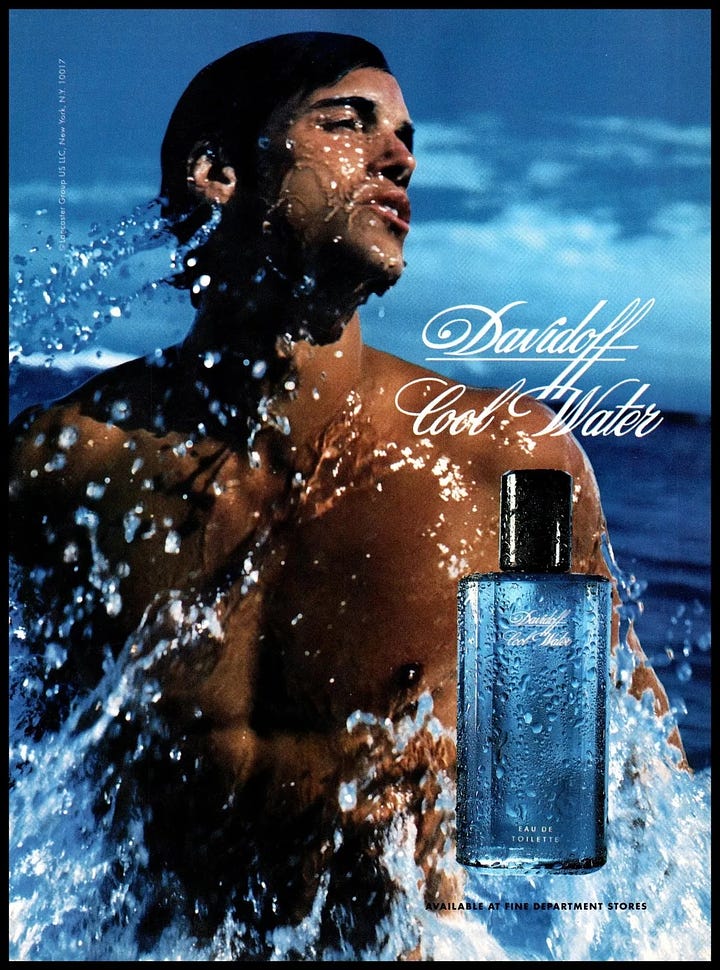

It’s clean, marine, with a hint of fruit and flowers. Like the sea without fish, like the breeze on a mountain top. Some people say it smells like ozone. When it became the key component in Davidoff’s Cool Water in 1988, the entire perfume industry changed.

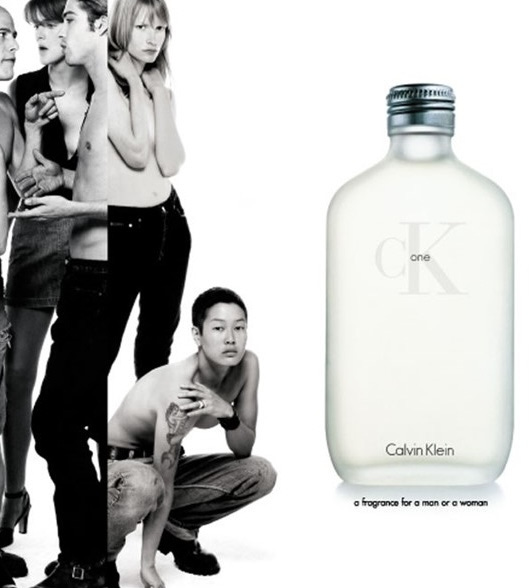

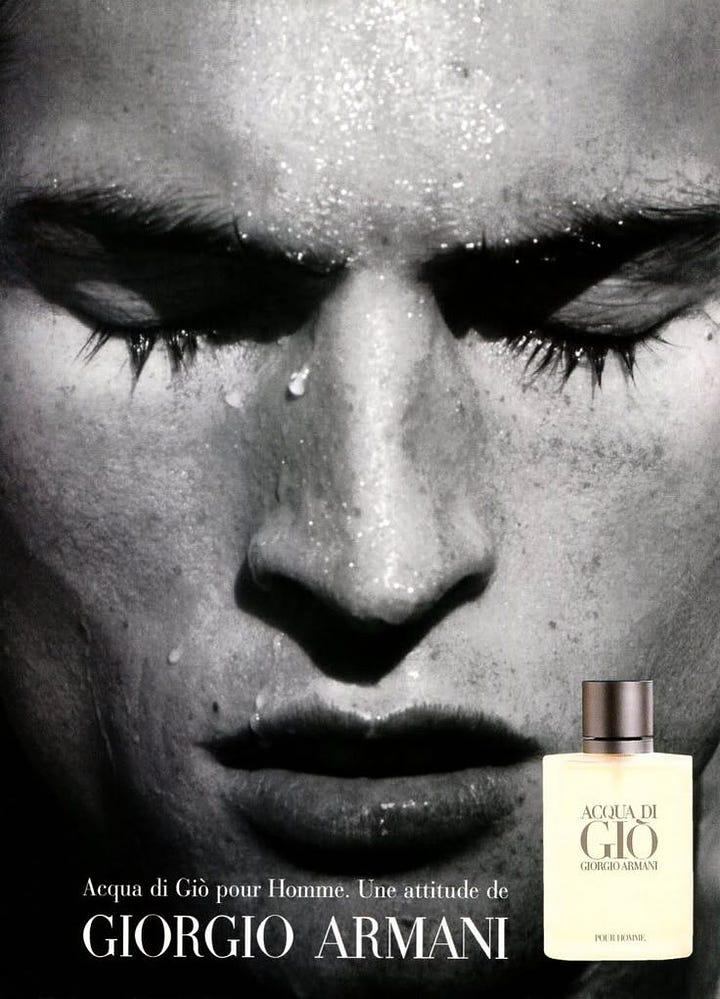

Before Cool Water, perfume was dominated by fougères, chypres, and orientals (I just learned these terms, they mean “lavender,” “mossy,” and “Old Spice” respectively1). But once calone hit the scene, perfume became dominated by “quiet” fragrances and “sport” colognes, such as cK One (1994), Giorgio Armani Aqua de Gio (1996), Dolce & Gabbana Light Blue (2001). Now, decades later, everything from shampoo to fabric softener includes calone and its “fresh” scent neighbors, with labels depicting sail boats and billowing clothing lines.

The other day, I caught a whiff of Aqua de Gio on a crowded metro car. My college boyfriend Gabriel wore it. Actually, he bathed in it. Smelling it again was like stepping through a portal.

I gripped the metro car’s pole. My hair blew back, my pupils dilated. Suddenly, I was in Plunkett Hall, a cement-block all-male dorm at Mercer University, with a 9:00 p.m. curfew for all female visitors. I was sneaking past the RA to Gabriel’s musty little dorm room, his cologne heavy in the air as I followed.

Back on Muni, I had to calm my racing heart rate. I checked over both shoulders. I don’t know which millennial male was wearing it, but fuck that guy for frightening me.

Smells are psychoactive. They’re one of the most powerful memory-making substances in our world, but until recently I’d only experienced them passively. I’m often blindsided by scent memories. A restaurant sends me a whiff of mom’s cinnamon rolls; honeysuckle transports me to my childhood in Georgia; a stranger on the subway smells like my fuck boi ex.

When I met scent expert Andrés Gómez Emilsson, he said that memory making can be much more active. He told me he uses jasmine to calm down, pear to recall New Year’s Eve, and fig to hallucinate.

“It’s a very simple hack, actually,” he said.

Meet Andrés

In 2020 Andrés Gómez Emilsson was worried about losing his sense of smell.

Reports were revealing COVID patients could lose taste and smell for weeks or months after infection.

“I have this long standing interest in qualia and mapping state-spaces,” he said, “If I lost this forever, I wanted to make sure I used it in earnest.”

You may know Andrés from his tweets about consciousness, DMT, and perfume, or his catalog of guided meditations on YouTube. He is also the president and director of research at Qualia Research Institute (QRI). His work is dedicated to mapping qualia—the subjective or qualitative properties of our mental states.

In his apartment in 2020, he began a series of experiments. “I had spreadsheets where I would try dozens of aroma chemical combinations, and then finely tune their precise volume or weight.”

He discovered fascinating chemical effects like illusions, (“When you add two things together, it creates a third thing that is completely different”), and flicker, (“If you add vanilla and pine together, first the vanilla asserts itself, and then pine. They alternate quickly without ever really mixing.”).

He found molecule combinations could have wave patterns, reverb, and harmony.

“If you take a base note that vibrates in a soft way, and add a kiki, high-frequency top note, they fail to synchronize. They don't blend into one gestalt,” he said. “But if you add a soft base note they easily come together. Iso E Super mixed together with the vanilla and pine, for example, allows them to blend into a soft creamy mixture.”

At QRI, Andrés researches consciousness. He explores the phenomenological binding problem, a question that asks how the human brain merges sensory inputs—like color, smell, shape, and emotion—into a unified experience. Essentially: why are you experiencing the universe from a point of view? Who is sensing the senses?

Andrés’ research at QRI overlaps with smell in this way. The parallel processing of the brain analyzes the pine and the vanilla simultaneously, but their vibrational quality seems to determine whether our mind perceives them separately or as a smooth gestalt.

“And this generalizes to other things. Different psychedelics come with different vibrational signatures on their visual tracers,” he said. “In that case though, we can actually measure the frequencies. But with scent, it’s still unclear, at least at the phenomenal level.”2

This uncharted territory could be a critical component of mapping consciousness—especially because smell is hard wired to the emotional and memory centers of the brain.

Smell and the Brain

Smell is very different from our other senses.

First, smell is attached directly to your skull. Your olfactory nerve is the shortest sensory nerve in your body. It connects the upper, inside part of your nose, the olfactory bulb, directly to the brain. Additionally, the roof of your nasal cavity is the cribriform plate, a perforated portion of the skull bone separating the frontal lobe from your olfactory hardware.

Second, smells are processed separately from other senses. Nerve signals for vision, taste, hearing, and touch are routed through the thalamus, the area of the brain responsible for directing sensory and motor signals to the cerebral cortex. The olfactory nerve, in contrast, is wired directly to the hippocampus and amygdala, areas responsible for memory formation and emotion.

This wiring makes scents potent memory makers. “Put simply,” write scientists Caro Verbeeka and Cretien van Campen, “the neural pathways are shorter and therefore faster.”

Because the olfactory system is directly linked to the hippocampus and amygdala, smells create strong “cognitive binding.” Cognitive binding stores sensory, geographical, and temporal inputs together to create contextual memories. This is why smell-induced memories tend to be more detailed, vivid, and long-lasting.

There is still debate in the scientific community about how smell actually works. Many argue scent molecules work in a lock-and-key system to attach to receptors based on shape. Others assert this is too simplistic, and scent molecules have a vibrational signature that could be interpreted by receptors through quantum mechanisms.

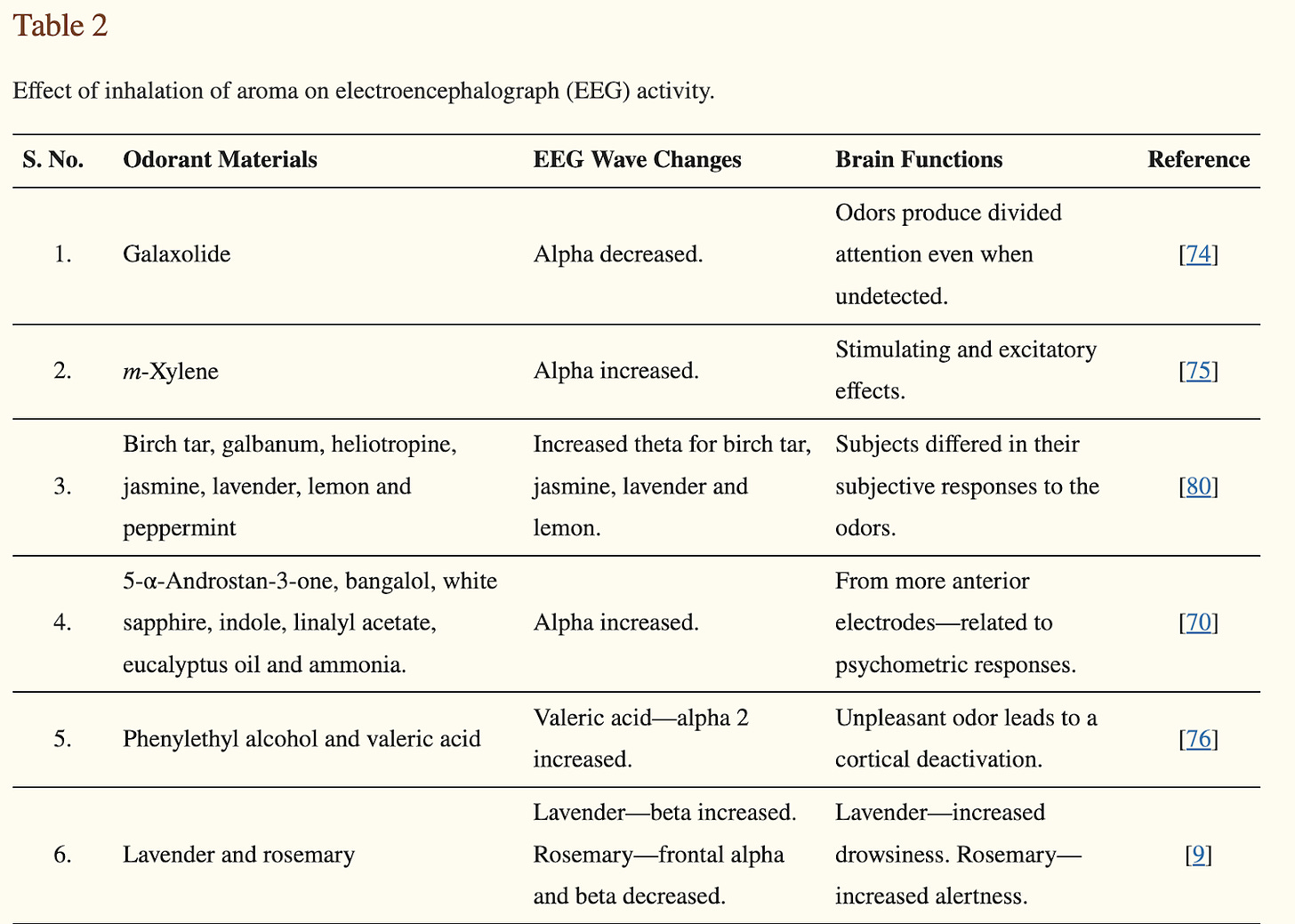

Whether or not you subscribe to the shape or vibrational theory of olfaction (lol), smells have an undoubted effect on human brain waves and hormonal regulation. Although the term “aromatherapy” has been co-opted and diluted by cosmetics companies, the neuroscience is solid and replicable. A 2016 meta analysis of the psychophysiological effects of smell found significant changes in alpha, beta, and theta brain waves in response to different scent molecules. Lavender and citrus were found to influence mood and stress. Rosemary and peppermint were shown to improve concentration, alertness, and memory recall.

Andrés has experienced and experimented with this phenomenon directly.

“I was experiencing quite a bit of fear on a meditation retreat. And my subconscious actually said, ‘Hey, here are some scents to cancel out the fear.’”

“It was not voluntary. But a part of me was investigating subconsciously. If fear has a vibration or a rhythm to it, then there should be a scent vibration that would massage that fear away.”

After some tinkering, Andrés created “Fearless,” a scent with a soothing vibrational quality that consistently worked to keep him calm and courageous during deep meditation. It contains banana, honeydew melon, jasmine, and mint. “From a perfumer's perspective, it is a pretty weird smell,” he laughed, “but it is not bad.”

“The idea there was to disrupt associations,” he said. “Instead of evoking memories, I wanted to experience a direct counter to the ungrounding vibrations of fear. What my subconscious concocted ended up being a very grounding soft, smooth, sweet, fresh and calming set of olfactory (phenomenal) vibrations.”

But what if the vibrations aren’t soothing?

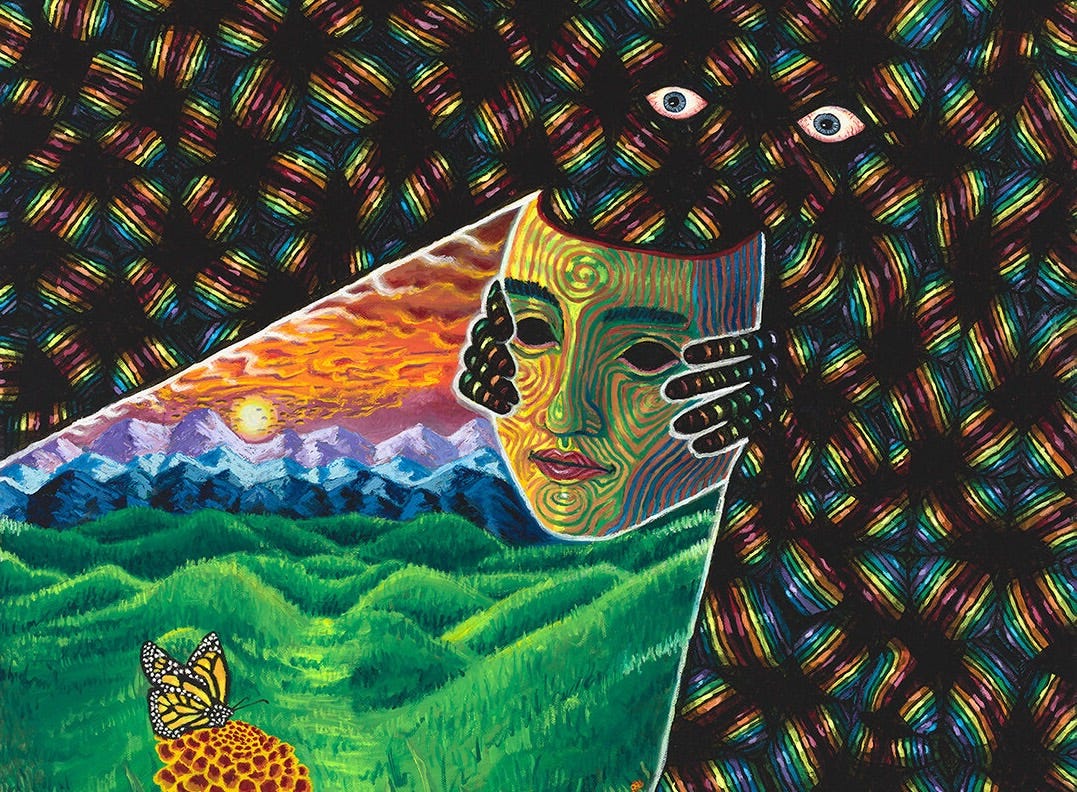

“There was one perfume called Noble Fig by Ferrari. It smells kind of sweet, but it's also quite stringent,” Andrés said. “I was wearing it on my shirt, and in meditation I started having very spiky visual hallucinations. It looked like a coily, ferrofluid.”

It was disturbing, and very distracting. He got up, changed into a new perfume-free shirt. “I applied Fearless, and within three minutes, that hallucination was gone,” he said. “I was in a world of complete softness and friendliness. It really worked.”

Because smell is so strongly bonded in the brain with the temporal aspects of memory and emotion, scents have powerful psychoactive effects. And, Andrés said, these effects are well within your control.

Like our other senses, smell is plastic.

Over the course of this series we’ve learned that listening to music can improve your ability to hear, overriding predictive processing allows you to see with more clarity, expanding your somatic awareness deepens your sense of touch, and understanding flavor improves your sense of taste. The through line is clear: pay attention.

We can improve our quality and depth of experience simply by paying attention. Our senses are profoundly acute. We receive an overwhelming amount of sensory information at all times. To cope, most of us tune our senses down (or off). Being overstimulated or overwhelmed gives us the ick. I feel this often. Too touchy, too smelly, too loud. But by disassociating from our senses we lose the reflex to turn the volume back up. Writing this series has taught me that correcting course is totally possible. We are in control of the volume knob. With thoughtfulness and intention we can truly transform our world.

All that to say: pay attention to your nose. All it takes to get better at smelling is practice.

Improving Your Sense of Smell

After our interview, my head was spinning with Andrés’s spectacular lexicon and inventory of smells. “Waxy,” “voluptuous,” “dry,” “clear,” “spikey,” “creamy,” “mushroomy,” “harmonic”.

I was feeling a bit overwhelmed, honestly. I’d looked through a keyhole into a labyrinth of knowledge. Centuries of history from Sumerian resins and ancient Egyptian enfleurage, to secret formulas for Catherine de Medici and perfumed courts at Versaille. I wanted to get better at smelling, but I didn’t necessarily want to become a chemist or historian.

Andrés reassured me there is a much lower bar to entry. For him, scent chemicals were a way to map a rich new topography of human experience.

“Places I visit now have a new sense of depth,” he said. “It enriches my life.”

You don’t need to memorize molecules or make spreadsheets of formulas, he said, you just need practice.

With that in mind, I took myself on a field trip. I tracked down a perfume shop in San Francisco called Ministry of Scent. I walked in with a notebook and a boba tea. “Hello,” I said. “I need help.”

I explored the store for hours with the two expert perfumists on duty, Sky and Selina.

“Ok. What does ‘creamy’ smell like?” I asked.

Selina hefted a cut glass bottle, spraying a perfume with vanilla and heliotropine. I breathed it in, feeling the richness, the softness, like custard.

“Now, what does ‘fougère’ mean?”

Sky offered an amber liquid with lavender and coumarin. The scent was like a sun dappled forest floor. Herbaceous, mossy, slightly bitter.

Every time I smelled something and gave it a name, it was like a window opened. I would inhale and simply…understand. It was as if a new color was added to my spectrum of visible light. Like I’d seen it all along, but suddenly the lens focused.

Sky took me to a back wall lined with bottles of “accords”—the building blocks of perfume. All the celebrities were there: linalool, labdanum, vetiver, aldehyde. I even got to smell the famous calone itself.

Huffing different formulas, the illusions of iron, leather, and amber vibrated across my olfactory bulb. Beyond the quantum chemistry, I began to understand the art of it.

Perfume critic Tania Sanchez writes, “Perfume really is an art, not a science. Perfumes have ideas. Some are facile and some are complicated; some are representative, some abstract.”

And that’s the thing: smell is abstract. You can’t touch it or see it or hear it. We have to rely on associations and allegory. It’s difficult to ascribe a concreteness to an otherwise invisible sensation. “Direct experience is the only experience,” writes Sanchez.

Learning to smell is learning to recognize and label sensations. When you learn a language you ascribe a word (“soccer ball”) to a form or concept (soft sphere used for sports), so that you can communicate your thoughts and needs to other people. What I learned in Ministry of Scent that day was clear: I needed vocabulary.

Writing this series has shown me that we analogize our senses to each other. All the wires are crossed. Sounds have texture. Textures have flavor. Flavor has color. And the same thing goes for smell.

At home, with all the bottles and scent strips fanned out around me, I started developing a lexicon.

First, there’s taste. Smells are creamy and sweet like vanilla, or spicy like nutmeg and ginger. Scents also have color: green is earthy or grassy, white is floral like gardenia and jasmine. Next is touch. Smells have texture: woody notes like pine feel sticky; pepper or juniper feel sharp and prickly. They also have weight: heavy and rich like cognac or chocolate; light and herbaceous like peppermint or basil. Lastly, sound. Like Andrés said, smells are like music, vibrating chords and harmonies. A fragrance with lemon or grapefruit is buzzy. Patchouli and clove are loud; iris is whispery.

As I developed these metaphors, I was strengthening the cognitive bind of words and smells. By linking them to more tangible sensory experiences, I found I could more easily articulate the nuances.

But, listen. If you’ve gotten this far and you’re like, nah this is too much work, I hear you. And I have a counterpoint.

Memory Hacking

Instead of studying the art of perfumery, you can just hack it.

“A memory hack I highly recommend is super simple to do,” said Andrés. “If there is one day that you want to remember very uniquely, choose two or three scents that you have never put together.”

This can be an essential oil, an after shave, or a cologne at the back of your medicine cabinet.

“That day you spray them together. Whenever you make that combination again, you'll address that specific day.”

Andrés looked off to the left, calling down a scent memory from his past. “New Year's Eve before 2020, for me, smells like pear and violet,” he said smiling. “That was the first time I ever smelled it and just got completely imprinted. You can be very purposeful about it.”

This gave me hope. Because despite all my field research, I was still haunted by calone, and all the water perfumes of the 2000s. Maybe with more intentional memory hacking, I would be able to recognize these old smells with tenderness, rather than be affronted on the metro.

So, I took myself on a second field trip, this time to Sephora. As the automatic doors slid open, I could already see the bottle on the shelf.

I took the glass body of Aqua de Gio into my palm, and put the metal atomizer under my septum. I cradled it for five slow breaths, holding the memory close. Plunket Hall. 2005. A supercut montage of Gabriel played on the back of my eyelids. I shivered.

In Perfumes, The Guide, author and olfactory scientist Luca Turin describes calone and “water” perfumes as “the fragrance for men and women who do not like fragrance.”

I remember feeling sheepish about Gabriel. I knew sneaking around to his dorm room at night was fucked up. We didn’t acknowledge we were sleeping together by day. He barely looked at me in class. He didn’t tell his golf teammates about me. A situationship, clearly. But this was long before that term was coined, so I didn’t have a name for it. It just felt bad.

Turin writes, “[Calone] perfumes are a slew of apologetic, bloodless, gray, whippet-like, shivering little things that are probably impossible and certainly pointless to tell apart.”

I moved on to Light Blue by Dolce and Gabbana, this one was Ben. I chuckled to myself. Next, Allure Sport by Chanel, this was Matt. Each bottle was like an apparition. I walked up and down the aisle, pulling the marine fragrances off the shelf, smelling each ghost.

The thing about calone colognes is that they’re too clean. A memorable, imprintable scent needs asymmetry. “Otherwise it’s perfect, but meaningless,” Andrés said. “And this has big insights into consciousness.”

“When you interview people who experience moments of cessation [deep meditation states where everything blinks out for a moment], they actually have no memorable content because the experience is so perfectly smooth and symmetrical. There's just nothing to say about it,” he said. “There's just no content, no differences. And the same goes for smells. You can make a ‘perfect’ scent that has almost no information, no message.”

I picked up another blue bottle. I smelled orange, melon, freesia. I sniffed again. White musk, cedar, and vanilla. With each breath, the bottles showed me their homogeneity.

Turin continues, “This is stuff for the generic guy wishing to meet a generic girl to have generic offspring. It has nothing to do with any other pleasure than that of merging with the crowd.”

Remembering these exes meant I was also remembering myself. Recognizing freshman Emily among the water perfumes, tumbling down stream, desperate to play it cool. But I was dating guys who were as confused and bumbling as me. Guys who were trying to fit in with their sport cologne and hook up culture aloofness. Those relationships had been as Andrés and Turin described: no content, no meaning.

I huffed each scent, searching for the sounds and textures. Each tone that I could hear ringing on its own gave me a sense of joy and recognition. Ah, there you are freesia. Mmm, hello iris.

I put down the last bottle feeling a sense of triumph. I could parse the colognes’ components, understand their different facets. These perfumes were too smooth and generic. They didn’t represent my life anymore. I’d grown into someone prickly, spicy, sweet—someone more interesting, asymmetric. Thanks to Gabriel I’d learned the hard way to respect myself, take up space, demand to be seen and heard.

It was like Andrés stripping off the fig perfume, and spraying on Fearless. I was taking back the power these old colognes had over me. No longer would they blindside me on the subway.

I walked out of the store and inhaled deeply, feeling the ocean air stream into my nostrils. Not a calone simulacrum. Real, salty Pacific air.

I took out a new vial of perfume, rose with leather and musk, and sprayed it on my wrists. I would remember this day.

.

Stay tuned for the full conversation with Andrés, publishing next week! Did you miss the previous episode? Read the How to See essay, and watch the How to See podcast/video interview. See the full series here.

The vibration theory of olfaction states that the vibrational frequencies of a molecule are key features that trigger receptor activity. The “phenomenal frequencies of scent” are different from the vibrational olfaction theory. “Phenomenal” meaning “perceptible by the senses or immediate experience,” which describes what the high or low frequency of the sensation itself feels like.

“In principle, the receptors that get activated with high molecular vibrational frequencies could correspond to low phenomenal frequencies and vice versa,” Andrés specifies. “The mechanisms that trigger receptor activity and the feeling that a certain sensation is ‘high pitch’ can be neatly separated. Studies have found consistency in people's judgment of these phenomenal frequencies, which show that there are above chance and cross-cultural associations between scents and frequencies of sound!”

See: Crossmodal matchings between odors and pitch

Re footnote 2: the relation is probably between molecular weight and pitch.

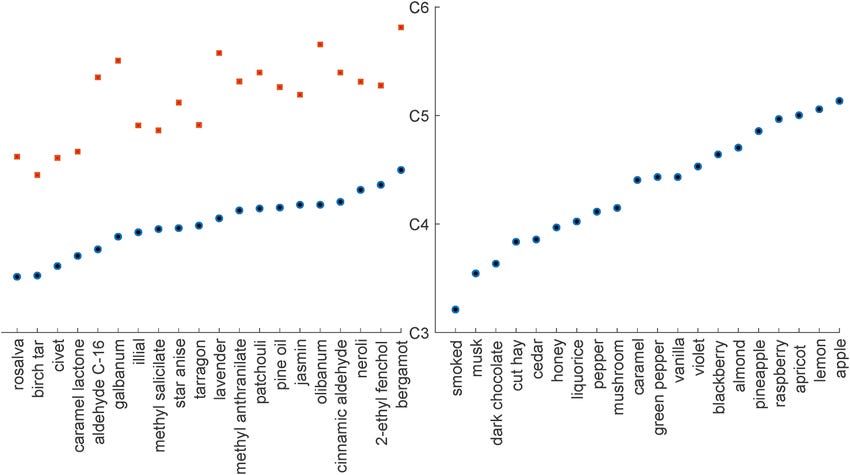

On average volatile or lighter molecules penetrate (saturate?) the olfactory membrane faster. Look at this chart of ester odors:

https://jameskennedymonash.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/table-of-esters-and-their-smells-v2.pdf

On there, the lighter (top left) molecules correspond to the higher notes (apple, pineapple) and as you go heavier in each direction you see honey, cedar, and chocolate.

Likewise, higher pitched sounds are perceived sooner than lower pitched sounds because it takes less sonic energy to trigger the receptor hairs - like how bigger strings make deeper sounds.

So the main correlation, if true, is likely to be that bigger molecules are perceived slower and so "sound" deeper.

This is mindboggling. Thank you for all the work you put into writing this. As always, you're killing it with these interviews and really warping my brain in the best way.